A Soviet-era monotown purpose-built around the Rustavi Metallurgy Plant in the 1940s, Rustavi is the perfect Tbilisi day trip for lovers of history, architecture and urbexing.

Or for a real adventure, spend a night at the surreal Soviet-era Hotel Rustavi like we did earlier this year.

Georgia’s third-largest city is best known as the home of the largest used car market in the Caucasus, and the last race track built in the USSR (completed in 1978).

But it’s the industrial heritage and Soviet city planning – specifically the Empire architecture, the mosaics, the Metallurgy Factory and the Brutalist apartment blocks – that makes Rustavi one quirky place in Georgia that is worthy of a visit.

Rustavi is definitely a blast from the Soviet past, but don’t mistake it for a place that is frozen in time. Just like Chiatura and Tskaltubo, this is an evolving city that is full of life.

And needless to say, the city’s history reaches farther back long before Stalin’s industrialisation plans took root (at least to the 4th century AD), as evidenced in the ruins of Rustavi Fortress and catalogued at the local History Museum.

Here are 12 of the best things to do in Rustavi – ancient, old and new – organised into an easy one-day itinerary.

Good to know: Rustavi has no connection to Shota Rustaveli, the legendary Georgian poet. He is associated with a different Rustavi, the small village in Meskheti region outside Akhaltsikhe.

Please note: This post contains affiliate links, meaning I may earn a commission if you make a purchase by clicking a link (at no extra cost to you). Learn more.

How to get to Rustavi from Tbilisi

Rustavi is located 30 kilometres – just under an hour’s drive – southeast of Tbilisi. Another 40 minutes by road, and you’ll arrive at the border with Azerbaijan and the Red Bridge Customs Post.

Note: The Georgia-Azerbaijan land border is only open to outbound travellers – i.e. you can travel out of Azerbaijan and into Georgia by foot, but not vice versa. The only way to enter Azerbaijan is by flying. This has been the case since 2020. Restrictions will remain in place until at least July 1, 2024.

Rustavi is part of Kvemo Kartli region. The city is best accessed from Tbilisi or from Kakheti wine region via a shortcut through Gamarjveba.

If you have an off-road vehicle, you can combine a visit to Rustavi with the David Gareja cave monastery complex and ‘rainbow hills’ in Udabno.

Tbilisi to Rustavi marshrutka

The easiest way to travel to Rustavi from Tbilisi is by marshrutka van. Plenty of people live in Rustavi and commute to the capital for work or study, thus connections are very frequent. Vans generally run every 10-15 minutes between 7am and 11pm.

Journey time to Rustavi is 50 minutes (potentially longer if there is traffic), and the fare is 2.5 GEL per person (paid in cash to the driver).

There are several departure points for Rustavi buses: from in front of the Sports Palace in Saburtalo, from Didube Bus Station, and from Isani. I recommend picking up a yellow van at Station Square in front of Tbilisi Central Railway Station. Drivers wait at the bottom of the ramp in front of the station building, footsteps from the Station Square metro station exit.

Once in Rustavi, vans travel down the main street, Megobroba Avenue, then across the river. To follow my itinerary, I recommend alighting at the big roundabout with the Shota Rustaveli statue at its centre (see the location here).

When it comes time to return to Tbilisi, simply flag down any marshrutka van travelling the opposite way. Your best bet is to wait at a bus stop on Megobroba Avenue where vans slow down for passengers, giving you time to read the sign on the dashboard.

Vans terminate at different points around Tbilisi. For a Station Square van, look for the word ‘Sadguris’ and a metro icon on the sign displayed in the windshield.

Tbilisi to Rustavi train

Passenger trains connecting Tbilisi with Gardabani further south make a stop in Rustavi. This route is served by old commuter electro trains that stop frequently. The hard seats are not terribly comfortable!

Currently there are two daily trains at 7.10am and 7pm. Travel time is much the same as by road, around 50 minutes, and the fare is 50 tetri.

Rustavi Railway Station is located on the eastern side of the river, around 1.6 kilometres from the centre.

The station building dates to the Soviet era, when Rustavi was an important stop on the Baku-Batumi railway that ran parallel to the oil line. At present, there are no trains between Georgia and Azerbaijan, but hopefully this stage will reopen as part of the much-anticipated Baku-Kars Railway.

Tbilisi to Rustavi taxi

Taking a taxi to/from Rustavi is an affordable option. I recommend using the Bolt app to book a cab. Expect to pay 25-30 GEL.

How to move around Rustavi

Rustavi is completely flat and easy to navigate on foot.

The city is divided into two parts: ‘New Rustavi’, the residential microdistricts on the western side of the Mtkvari River (closer to Tbilisi), and ‘Old Rustavi’, the industrial-civic area on the opposite bank. I recommend starting on the western side, then using a bus to travel across the river to save time and energy.

City buses 2, 3, 4 and 6 all depart from in front of the Hotel Rustavi (see #2 below) then travel down the main street and across the river before terminating at the metalworks. Stops are clearly marked with shelters and electronic sign boards.

A single bus fare costs 50 tetri and can be paid for with a chipped debit card or your Tbilisi Metromoney transport card. Cash is not accepted.

Rustavi map

Here is a handy Rustavi map to help you organise your visit.

12 things to do in Rustavi

This itinerary is ideal for spending one day in Rustavi, starting in the microdistricts and culminating with sunset at the fortress.

1. See Soviet-era city planning in the microdistricts

When you arrive in Rustavi, the first thing you encounter is the towering Brutalist-style buildings that dominate the western side of the city.

Numbered one through 21, each microdistrict occupies a full city block and was designed to be its own microcosm, comprising residential blocks, shops, kindergartens, schools, and other public services.

This type of Soviet-era city planning is common throughout the former USSR and other parts of Central and Eastern Europe. I am very intrigued by this style of living, having visited similar neighbourhoods in Tbilisi (Gldani and Varketili), Bratislava (Petrzalka), and Vilnius (Fabijoniskes).

In Rustavi’s case, the apartment buildings are mostly uniform 9-storey blocks arranged around small green spaces. The layout of the city does not follow a strict grid pattern, rather some streets fan out from Megobroba (‘Friendship’) Avenue, which runs through New Rustavi towards the river at an angle. Majority of the construction was carried out after WWII by German POWs.

Arriving in Rustavi for the first time, conditioned by photos I had seen online, I was fully expecting the microdistricts to be a sea of grey, gristly concrete. I was wrong.

My preconceptions about Rustavi being ‘locked’ in a Soviet timewarp were gone once I saw that many of these buildings – still very much lived-in by thousands of families, by the way – have been retrofitted with new facades. This is also the case in other Georgian cities including Gori, Zugdidi and Zestafoni.

Even with the recent makeover, Rustavi’s Brutalist ‘commieblocks’ are still very impressive. Interestingly, little flourishes that clearly date to the Soviet period – bas-relief panels positioned high up on facades – have been retained and not covered over.

Wandering through this part of Rustavi, my first impressions were of a very livable, clean city: Tidy traffic islands, parks and the pedestrian-friendly avenue with its wide sidewalks.

2. Drop by the Hotel Rustavi (or stay the night)

New Rustavi centres on a traffic circle and monument of Shota Rustaveli. Directly off the square, you will notice a couple of buildings that break the mould and stand-out for their different configurations, including the circular-shaped Savane restaurant.

The most striking landmark is the Hotel Rustavi. A relic from the Soviet period and an exemplar of Brutalism, it opened on May 1, 1989 and has been trading ever since. The building has three wings and from the front, resembles an open book.

The pale stone facade (favoured by Georgian architects as a softer alternative to concrete) has a tall arch at its centre and is fronted by a flowing stone staircase and a water fountain with a very-Soviet sculpture at its centre.

The bottom level of the hotel contains a restaurant, signposted in both Georgian and Russian. Unfortunately it was closed at the time of our visit. You can, however, go inside the hotel lobby, which contains some very impressive art pieces.

A tall pane of coloured glass casts beautiful shapes on the glossy floor. A long, white relief sculpture on the back wall depicts a series of characters gathered around a sun symbol. One of the buxom women holds a pomegranate in her hand. If you visit Rustavi in late summer or autumn, you will see a proliferation of pomegranate trees around the city.

Several rooms open up off the lobby, including a hair salon and a small sewing workshop. Curious, we wandered into the latter. The hotel’s resident seamstress proudly showed us a wall mounted with hundreds of stuffed animals. We speculated that they are children’s toys left behind in the hotel over the years.

The Hotel Rustavi is a working hotel. If you have time, I highly recommend spending a night here. We stayed in one of the mid-range rooms and were very impressed with the facilities – it was a much more comfortable stay compared to another Soviet-era hotel experience I recently had at the Sevan Writers House in Armenia!

Our room had a sitting area, a separate bedroom, and a generous ensuite bathroom. We also had a small balcony with terrific city views. Rooms are fitted with AC, and we were surprised to find a kettle and two bottles of complimentary water. Staff at reception were very sweet and gave us a free late check-out the following morning.

Prices range from 70 GEL to 120 GEL a night. We paid 100 GEL. Reserve a room at the Hotel Rustavi here on Booking.com.

3. Stop by Rustavi Sioni

Located just off the roundabout in the 9th Microdistrict, Rustavi Sioni (or Rustavi Assumption Cathedral) is the city’s main Orthodox church. Given that Rustavi was developed during the Soviet era when churches were not exactly part of the plan, this temple is very young – it was consecrated in 2011.

There are several things that make this church noteworthy. For its construction – a decade-long process led by Temur Burkiashvili – residents of Rustavi, most of them lay people who learned on the job, were chosen as builders. From start to finish, they followed traditional 11th-century architectural tenets, transporting, cutting and carving the stone for the facade and interior completely by hand. They also used egg yolk as a construction material.

The church’s cross-shape design and facade are inspired by Nikortsminda Cathedral in Racha, while the use of sandstone echoes both Svetitskhoveli Cathedral in Mtskheta and Anchiskhati Basilica, the oldest church in Tbilisi. A gallery of arches wraps around the base of the church like a skirt, and is in turn encircled by gardens and a high wall.

Embedded in the microdistrict, large apartment buildings hang over the church on three sides, giving it a very striking backdrop.

Take a walk around the church and note the collection of wooden baby cradles in the yard. We stumbled on a very picturesque scene at one of the ancillary buildings: Holy robes hung out to air on a beautiful carved wooden balcony.

4. Cross the river & compare the architecture in Old Rustavi

Rustavi’s two halves each have their own character. As you cross the Mtkvari River (either by bus or on foot), you will notice the difference almost immediately.

(The area between the last microdistrict and the bridge is a bit of a deadzone, so I do recommend using the bus to save time.)

While pared-down Brutalism dominates the microdistricts, the ‘Old’ side of Rustavi is more ornate, more decorative. There are some lovely examples of Stalinist Empire architecture in the buildings with grand loggias, belvederes and pretty plasterwork.

Highlights include the Rustavei Mayor’s Office, the Drama Theatre, the Musical School on Rustaveli Street (above right), and the Railway Station.

Head straight down Megobroba Avenue and you will meet Rustavi’s Freedom Square. Unlike its cousin in Tbilisi, it is actually a pedestrianised piazza. The fan-shaped mosaic pavement is identical to the one at Fountain Square in Baku. A section of the long, narrow park that runs through the city towards the metallurgical plant (see below) is named after Heydar Aliyev, so I’m quite sure Azerbaijan had a hand in modelling this part of Rustavi.

Adjacent to the square, in front of the Mayor’s Office, there is a copper orchestral ensemble led by a conductor. The characters were created by sculptor Levan Bujiashvili, the same artist responsible for the bronze figures dotted along Rustaveli Avenue in Tbilisi.

During the middle part of the day, the effect of the sculpture is amplified by the cool shadows each musician casts on the pavement.

Continue down the avenue and duck into some of the residential backstreets. You will find beautiful Georgian-style courtyards hidden behind some of the facades, and every now and then a retro car parked on the curb.

Megobroba Avenue extends all the way through Rustavi. After Freedom Square, it turns into two parks, Kostava Park then Heydar Aliyev Park.

5. Admire the grand Rustavi Metallurgical Plant

After around 20 minutes of walking west through the twin parks, you will come to the Rustavi Metallurgical Plant.

This massive factory complex marks the eastern frontier of the city. Most of it is invisible – you can just glimpse the tops of smokestacks in the distance – hidden behind a grand facade.

Debatably the most crucial building in Rustavi, the Rustavi Metallurgical Plant is the whole reason the modern-day city exists. Founded in 1941 when heavy industry was top of mind under Stalin’s five-year plan, it was the first metallurgical factory in the Caucasus to produce seamless pipes from iron and aluminium. Such pipes were primarily used on the oil fields in Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan.

The first steel was produced here on April 27, 1950. At its peak, the factory employed around 15,000 people. Its core group of workers – 5,000 young men from across Georgia, all of whom were born in the year 1926 – were ‘mobilised’ to kickstart the plant, trained in similar facilities in Ukraine and Russia before being assigned to Rustavi. It was for them and their families that the monotown was developed.

Like the Zestafoni Ferroalloy Plant which was inaugurated in October 1933, the Rustavi Metallurgical Plant is still functioning today – although at a fraction of its original capacity. It employs around 1,200 people.

This is important to keep in mind when visiting. The factory is private property and photography is technically prohibited. We were approached by a very friendly guard who gingerly asked us not to take photos of the facade. I know other travellers who have approached the building without issue, and I have even heard of a few people being invited inside for an impromptu tour.

Feel it out for yourself. Admiring the facade from a safe distance (and taking some sneaky photos) might be enough for you.

Between the park and the first building, you will see three busts and a sculpture depicting a trio of workers – a young man, an older man and a woman – working over a smelting pot (pictured above). Then the plant’s five-storey facade comes into view from between the pomegranate and plane trees.

A typical Soviet construction, it is extremely grand – in a different context, you might think it was a theatre or a railway station. Two wide bands of stone bas-reliefs run across the front, depicting a typical array of workers, industrial motifs and astrological symbols.

To the right, there is a plant hospital and to the left, the old Institute of Automation. Walk around to the left, through the carpark, and you will enter a small courtyard between the office buildings where there is a well-kept mosaic panel.

An empty plinth in front of the mosaic was probably once topped with a bust of Lenin or Stalin.

The area around the plant is very interesting, so I encourage you to explore the area if you have time. To the north, along Yuri Gagarin Street, there is a fire station and on the opposite side of the road, the Soviet-era Kikabidze restaurant has some weird sculptures in its internal courtyard.

The Metallurgical Factory is Rustavi’s biggest production facility, but in reality it was just one part of an industrial network that spanned approximately 90 plants, ranging from ironworks to chemical factories.

6. Visit the Rustavi History Museum

After the factory, start making your way back to the centre of Rustavi, arcing around to the west.

The Rustavi History Museum is very typical of small local museums in Georgia: slightly shabby, but with a passionate staff and some real treasures on display.

Established in 1950, just a few years after the city itself was laid out, the museum traverses Rustavi’s history from the Middle Bronze Age through to the Soviet period. The most interesting exhibits for me are the ones on the upper floor that cover the Metallurgical Plant and the sister industries (including a nylon fibre factory and a fertiliser factory that utilised plant waste) that emerged around it.

Unfortunately, the museum has a no-photography policy, which may or may not be enforced depending which staff member is on duty. Entrance costs 5 GEL per person, and you can hire an English-speaking guide for an additional 20 GEL.

The museum is open from 10am until 6pm, Tuesday to Sunday (closed Mondays and holidays). Note that the entrance is on the side of the building, via Givi Odisharia Street.

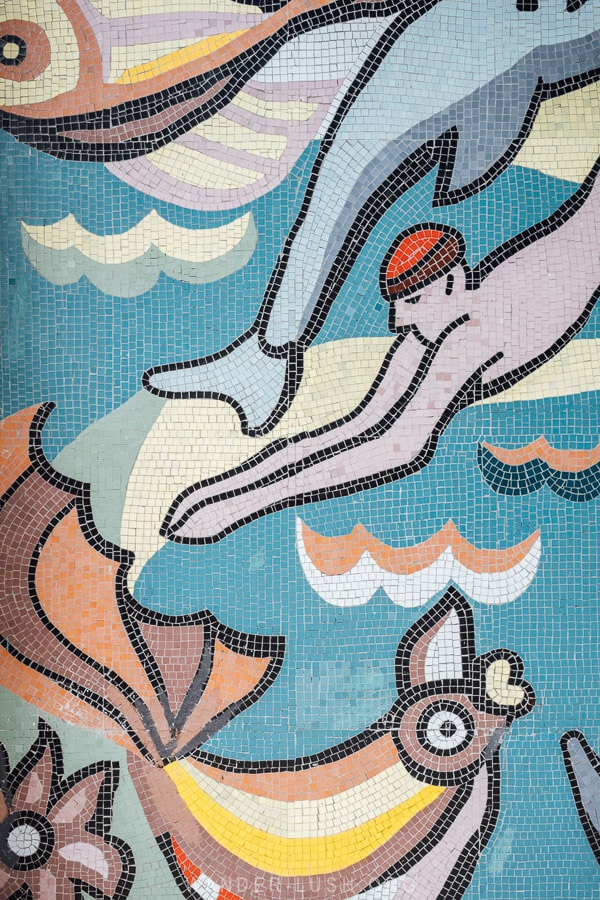

7. See the incredible swimming pool mosaics

Next door to the museum, there is an indoor pool complex that sports one of Rustavi’s finest Soviet-era mosaics. Named Toila (‘seagull’, like the popular ice cream brand), it is completely unsuspecting from the outside.

My various mosaic expeditions around Georgia have taught me that indoor pools often have the best large-scale mosaics of all. The huge Poseidon panel at the swimming pool in Zestafoni is among my favourites. In Chiatura, there is a terrific Jason-and-the-Argonauts-inspired mosaic, and although I am yet to see it in person, the pool mosaic in Zugdidi looks similarly impressive.

I was desperate to see Rustavi’s indoor pool – but when I noticed people filtering in with their sports bags in hand, I was worried that I wouldn’t be allowed in. We approached the lady at the front desk and sheepishly enquired about the ‘mozaica’. At first she misunderstood my broken Georgia and pointed me back towards the museum. But then she cottoned on and promptly handed over two pairs of blue plastic booties for us to slip over our shoes.

We donned them and made our way upstairs, past the locker rooms and into the pool area. There were several people swimming laps so we had to be careful not to get in anyone’s way. A swimming coach and several spectators approached us as we made our way around, very surprised that we were interested in their old mosaic!

The mosaics extend along both ends of the pool. On one end, the designs of swimmers and people playing different water sports are cartoon-like with hyper-saturated colours.

On the other end, the images of Jason and Poiseidon are more muted in tone and stylised. This composition mirrors other swimming pool mosaics in Georgia almost to a T.

I haven’t been able to find the authors or dates of this mosaic – if you know, please leave me a comment so that I can properly credit them.

8. Stop by the stadium

Continue walking down the main street and you will come to the gates of the Rustavi Metallurg Stadium. This is the home of football club FC Rustavi, which was known as Metalurgi during the Soviet period.

As an aside, the way Soviet football teams were created and named is fascinating – here is a good breakdown. Briefly, professional footballers did not exist among the ‘workers of the world’, thus all players were officially employed and paid by various industrial enterprises, with the clubs named in reference to their activities.

Some examples from Georgia: Tbilisi’s FC Locomotive was associated with the railroads, Chiatura’s FC Magaroeli was connected to the mines, and Kutaisi’s FC Torpedo was founded at the automotive factory. Of course it makes sense that Rustavi’s local team was named after the steel mill.

Fronted by columns and arches, with a grand metal gate with a soccer ball suspended in a metal ring, it is a very old-school stadium that I assume will be reconstructed (or completely replaced) in the years to come.

Duck through one of the open gates to walk among the bleachers.

9. Find Rustavi’s modern street art

As I have mentioned, Rustavi is not the stagnant Soviet city many people imagine it to be. It is a changing place, and one of the ways this manifests is in the street art scene.

There aren’t as many murals in Rustavi as there are in Batumi or even small cities in the west of Georgia such as Kutaisi or Ozurgeti, but Rustavi does have some excellent street art that is worth tracking down. Many of the murals were created in 2019 by the Niko Project.

My favourites are ‘Rustavi Elefant’ by German-born Lion Fleischmann (below left), and ‘Girl in a Bush’ by David (below right). Find the locations marked on my Rustavi Map, linked above.

This mural of a little girl on a swing wearing a gas mask and with blistering smokestacks in the distance (pictured above) is clearly a comment on Rustavi’s controversial industrial legacy.

There are several more works, including a vertical fish mural by Dr. Love, on the side of the Rustavi Arts Centre inside the park (see #12 below).

I tried to find two more murals, ‘Rooster’ by Matthias and a toucan painting by Dante, both created in 2019, but I believe that they have since been erased.

10. Eat at Cafune social enterprise cafe

I first learned about Rustavi’s social enterprise cafe, Cafune, back in 2020. As well as employing and training probationers and ex-convicts, the space also functions as a gathering place for young people from Rustavi, aiming to foster community and creativity.

I love the mission, and I was always going to visit Cafune – but frankly I was blown away by the food and the setting. It was so good, every time I’m in Tbilisi I now consider making a special trip to Rustavi just to eat lunch here!

The cafe is located on the riverside and has a big outdoor terrace perched over some old stone ruins. The interior and glasshouse-like dining area are lovely too. The menu combines Georgian and light cafe-style meals, making it perfect for lunch.

We ordered the Kizikhian salad, a twist on the typical cucumber-and-tomato medley with the addition of pickled jonjoli, the crumbed chicken in walnut bazhe sauce with a side of green adjika and Georgian bread, and a bowl of mac and cheese. Everything was outstanding.

11. Walk in the Park of Culture and Rest & watch the sunset on the lake

After a meal at Cafune, cross the road to find the main entrance to the park off Megobroba Avenue (note that the park’s second entrance might be inaccessible due to a locked gate, as it was at the time of our visit).

Rustavi Park – also known by its Soviet moniker, the Park of Culture and Rest – has to be one of the loveliest city parks in all of Georgia. Following the curve of the Mtkvari, it extends south along the river. There is a long artificial lake at its centre, looped by a walking-cycling track that you can use to circumnavigate the lake. It takes around an hour to stroll the entire path at a leisurely pace.

Piers at the top of the lake tout pedalo trips on the water. On the eastern side, there are several Soviet-era buildings including the (partially abandoned) Art Centre, with its outdoor amphitheatre. You will also find a series of interesting sculptures dotted around the gardens.

I recommend walking around the park in an anti-clockwise direction, exploring the fortress ruins at the halfway point (see below) before making your way to the eastern side of the lake in time to watch the sunset over the water.

12. Traverse the ruins of Rustavi Fortress

The oldest surviving structure in Rustavi, the fortress sits within the boundaries of the Rustavi Park at the southern tip of the lake. Once part of a network of fortifications erected around Tbilisi to protect the capital, it was besieged in 1265 and only unearthed again in the 1940s when groundworks for the metallurgy plant were being laid.

The fortress is a must-see in Rustavi as it is the only obvious clue to the city’s pre-industrial past. Sources are sketchy, but it is believed that Rustvai – once known as Bostan-Kalaki or ‘the city of gardens’ – could have been founded around the 4th century BC. It served as an important administrative outpost for the Kingdom of Iberia, and the fortress dates to this period (around the 4th century AD).

Rustavi Fortress was noted for being the only fortification in Georgia with frescoes. Unfortunately there is no evidence of these left today. The fortress is merely a shell, made up of crumbling walls, the outlines of defensive towers, and inside the cylindrical outer walls, some old foundations.

At the eastern corner of the fortress, you can see a lovely reconstructed brick arch and the entrance to a tunnel that you can crawl through down to the waterway. The Mariini Canal, which was carved out at the same time as the castle, is visible from the eastern fortress walls.

Have you visited Rustavi? Share you comments/recommendations in the comments below.

You might also be interested in…

- The ultimate Georgia itinerary: Four detailed & custom-designed itineraries

- Georgia Travel Guide: All of my 200+ posts plus my top travel tips

- Georgia travel tips: 25 essential things to know before you go

- Places to visit in Georgia: 50+ unique & underrated destinations around the country

- The best things to do in Tbilisi: Favourites, hidden gems & local picks

- 35+ best restaurants in Tbilisi: Where to eat Georgian food

- 15 best day trips from Tbilisi: With detailed transport instructions

- The best time to visit Georgia: Month-by-month guide to weather, festivals & events